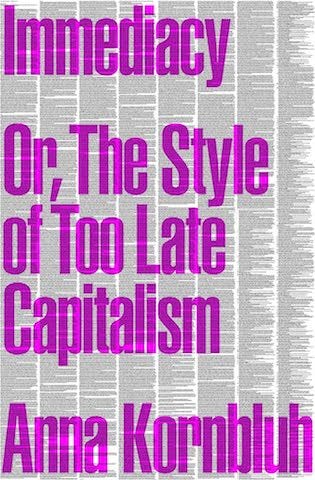

On Anna Kornbluh’s Immediacy

A review of Anna Kornbluh's recent book Immediacy: Or The Style of Too Late Capitalism

In her recent book Immediacy: Or, The Style of Too Late Capitalism, Anna Kornbluh makes the case that a dominant cultural style has emerged in the contemporary social, economic, and aesthetic worlds. In the arena of literature (she is a literary theorist) she finds that novelists, poets, and essayists seem to believe rather often that an apparently unprocessed, unfiltered outpouring of one's individual feelings, especially those related to trauma, identity, and a will to be seen and recognized, should trump more complicated, more artificially constructed, more stylized literary workings. Kornbluh has strong sympathies with Marxism and she suspects, and tries to demonstrate, that economic happenings in the culture will reveal patterns analogous to those in the aesthetic sphere. Many individuals today, instead of facing the economic machinery through the mediation of a long-term attachment to a particular company, are thrown back on their individual resources as freelancers and independent contractors signing up for temporary work assignments or working as Uber drivers and the like. Kornbluh notes as well that computerized financial trades happen immediately now and that packages are delivered not long after you order them. Items must circulate as rapidly as possible, whether they are industrial raw materials or finished products, and there is a “just in time” availability of parts for factory production lines, in a manner analogous to the instant texting of one's feelings, impressions, and experiences to others across the globe via social media. Videos and films, instead of provoking thoughtful reflection and delayed assessment, surge into one’s experiential space, says Kornbluh, with force and rapidity, with more scenes always insistently on the way so that such reflection does not occur. For Kornbluh, an increasingly privatized economy that puts greater economic pressure on individuals and that emphasizes ever faster operations and ever more efficient circulation will tend to generate literature of the type described above: individualized confessional outpourings of what is immediately felt and is relatively unstructured. Let us see how she gets there.

Her goal is not merely a descriptive one, not merely an attempt to lay out an interesting and distinctive cultural pattern. Her Marxist perspective sees this cultural style as an expression of a late, late capitalism that, in its privatizing and immediacy, has two very clear effects. First, it makes individuals less ready and less able to engage in critical reflection and in the application of sophisticated theoretical frameworks that would empower us to figure out what is wrong with our society and to change matters. Second, it prevents individuals from engaging in the kinds of activity and of thinking that promote social solidarity and collective action. It is experience mediated by reflection, by theory, by a personal distancing from one’s own experience, by a tentative exploration of alternative frameworks, and by linkages to larger social undertakings that must pave the way, she claims, toward a better future, not an immediate expressiveness of one’s subjective life that merely reflects the stances generated by late, late capitalist culture.

Kornbluh has a definite idea in which direction worthwhile literature ought to go. Instead of an unprocessed expression of private feeling, trauma, hurt, and resentment, it should take a much wider stance and explore today's socio-economic environment through the experiences of several diversely situated characters. Instead of reducing literature to first-person memoir and autofiction based on one’s private sensibility, it should develop traditional structures of plot and character development. Instead of offering only an immediate first-person present-tense stance, it should use third-person free indirect discourse to allow the narrator to explore the inner lives of many different characters at once. Instead of rejecting complicated, demanding aesthetic forms in poetry and literature in favor of the most immediate kinds of self-expression, it should accept how the admitted, transparent artifice of traditional structures opens up space for a mediated and more complex reflection on events. For there is, when such structures are used, no pretense of an unprocessed expression of feeling that is calling for our immediate empathy, identification, and full immersion.

Before an assessment of some of Kornbluh’s claims, it will be helpful if we are clear about distinguishing, as she often is not, the different kinds of immediacy and mediation that might come into play here, and their complicated interactions. Immediacy might mean that certain events follow one another without any temporal delay. Or it might mean that there are no agents or structures or events that intervene between two relevant happenings in a manner that shapes or distorts the relationship of those happenings. We can see how these two meanings might enter into some tension. Imagine an Indonesian small farmer who, in today's world, can use online programs to sell his produce to a food supplier in the Arab Emirates. This might be, let us suppose, one of the most mediated transactions in the world. The sale price is affected by currency traders in London, Zürich, and Hong Kong who are betting on or against the Indonesian rupiah. It might depend on soybean forecasts on the Chicago Board of Trade, on weather forecasts in grain-growing regions of Argentina and the Ukraine, and so forth. On the other hand, because of startling advances in technology that connect the world rapidly, the transaction might be an immediate one, with no delay at all. A very complexly mediated event happens immediately.

‘Immediacy’ might also refer to the particular phenomenological character of one's individual experiences. An experience may involve such a forceful presence in the here-and-now, whether it is an experience of oneself or of the world, that it presses upon us with little apparent processing, interpreting, or selecting on our part. Of course, both philosophical arguments and cognitive science experiments have shown that there is no true immediacy of that sort. Experience is always shaped, often unconsciously, by interpretive frameworks, editing strategies, preferences, and so forth. But there is a continuum such that certain experiences will be down at one end of it, where our conscious structuring is not much in play, and these can be called immediate. In the case of the immediacy that Kornbluh is most concerned with, the expression of very personal feelings of trauma, unacknowledged identity, and victimization, it should be clear that these are among the most mediated feelings one may have today. They are socially constructed and conceptually structured by some of the most powerful idea-frameworks and patterns of reinforcement circulating through the culture at the moment. Online social-media incentives as well as writing program incentives are set up to shape and reward just such so-called immediate feelings.

An immediate experience might also be one where an object, text, or event surrenders its meaning right away and unambiguously, not because there is no interpretation involved but because this interpretation, given one’s social and ideological situation, happens so automatically. Many students in a literature class, for example, when approaching even a very sophisticated literary text, have been so thoroughly trained in certain ideological positions that they immediately, without the slightest delay and in a predictable manner shared by many other students, pick out the racial and gender errors in the original text, its ways of devaluing and subjugating otherness. Such students can be like Mao’s Red Guard followers in the Cultural Revolution who were ready to interpret any social situation by quoting from his writings. Maoist ideology certainly was a powerfully mediating framework that massively shaped one’s everyday experience, but indoctrination, reinforcement, and habit can turn even a complex mediating framework into an aspect of an immediately given experience. (I will be asking later if Kornbluh’s own theoretical mediation sometimes acquires the kind of taken-for-granted immediacy that she is writing against.)

Another form of immediacy is presented quite nicely by Kornbluh. She describes the kind of apparently unprocessed confessional outpouring that carries with it a moral claim against any attempt by others at judgment or negative assessment. So long as I am describing my feelings and my painful experiences in an unadorned, honest manner that does not deploy artificial theory structures or interpretive schemes, then this is my voice and these are my feelings and any questioning of them is a form of hate speech that cannot be morally allowed. Because these confessional statements are so direct, immediate, and personal, they supposedly do not yet enter into the arena of claims that can be assessed and criticized from a more impersonal standpoint.

Historically, there is a form of immediacy related to that one; we owe it to the philosopher Kierkegaard. He rejected the idea that his relation as an individual to the divine should be mediated through the hierarchy, institutions, and sacramental practices of the Christian church, a mediation shared with countless other believers. Instead, so he claimed, his relation to the divine was characterized by a directness and immediacy that made this relation incommensurable. The address of God to the individual was a personal experience that could not be shared in any collective undertaking or even communicated to anyone else. In some respects, though evidently not in others, those making their highly personal confessional statements today are repeating Kierkegaard’s claim to an incommensurability that will not allow for collective scrutiny and assessment.

Kornbluh adds further identifiers in her account of immediacy. The experiences she is concerned with, she says, whether in literature, film, social life, or social media, are those that encourage, indeed nearly require, immersion and absorption. One is so enveloped by the experience that there is no space for critical distance, for weighing and comparing, for placing matters in larger, more revealing contexts, and so forth. She mentions as well, especially in the area of visual expression and the visual arts, the use of a rapid and almost assaultive succession of images so that viewers are too viscerally engaged to be able to step back and raise any intellectually or morally complicated considerations.

Kornbluh tries to refine her notion of immediacy, quite plausibly, by examining the process of mediation. The general idea she wants to focus on, when speaking of mediating processes, is an attitude towards one’s experiences that, instead of involving thorough absorption and immersion, allows for distance, conscious framing and interpretation, critical assessment, a consideration of alternative views, and a pressure toward a more impersonal, less parochial, less subjective stance. One version of such a mediation of experience that she does not give sufficient attention to is the straightforward Enlightenment practice of rational scrutiny, evaluation of evidence, critical assessment of arguments, and so forth. I believe that such a familiar Enlightenment practice, rather than the esoteric Lacanian and Marxist theorizing that Kornbluh ends up appealing to, is what is needed today in order to make us as a nation more responsible and more effective in our habits of testing and justifying what we believe. She underplays that aspect of things, I think, because her Marxism is much shaped by the Frankfurt School work of Adorno, Horkheimer, and Benjamin. These thinkers in their critical theory do not see Enlightenment practices of rationality as genuinely liberating but rather as entrapping humans in new forms of coercion and dominance: these coercive forms supposedly shape individual mental life so as to make happiness unlikely. So, that notably effective Enlightenment style of mediation is devalued in favor of something closer to the critical theory of the Frankfurt School itself, such that only far more radical transformations of society than those offered by Enlightenment critique can be valid. (A more recent member of the Frankfurt School, Jürgen Habermas, offers greater support for those Enlightenment practices.)

If one is to consider her perspective on mediation in a Marxist perspective, one might benefit from turning first to Hegel, who in a real sense set up this discussion space for Marx and others. Hegel is especially concerned, in his political philosophy, with the way that cultural institutions and forms of life can serve as enduring middle-level entities that join together two extremes. At an upper extreme are highly abstract notions of reason, autonomy, self-determination, justice, and happiness. At a lower level are the basic inclinations and desires of individuals. The latter level Hegel calls a sphere of immediacy. By this he does not mean that which occurs right away or in an unprocessed rush of experience but rather the ordinary wants and tendencies of individuals insofar as these are undeveloped and merely given, so that they are disordered, poorly arranged into useful mental coalitions, and moved about by arbitrary, external triggerings rather than by anything like rational autonomy. What is needed is a confident, enduring culture with strongly habituating institutions and practices, a culture willing to train and discipline its citizens, and especially its young, in the virtues and capacities needed to live a satisfying and admirable human life in that culture. Hegel is no friend of immediacy, then, as were some of his university friends involved in the Romantic movement. Individual inclinations, feelings, and desires left on their own in an undeveloped stage ultimately bring about, for him, an empty, arbitrary, and disordered existence too easily affected by chance stimuli from the world. He does recognize how the imposition of disciplinary practices on the population has historically been, very often, a matter of arbitrary force and dominance. But the Greek polis and, so Hegel importantly believes, the modern liberal parliamentary state can be models of a powerful mediating entity that, in shaping and disciplining its citizens and its young, in forming their mental and ethical lives in a certain manner, is working to give a concrete embodiment to abstract ideals of autonomy, reason, and justice. Citizens are not just being coerced; they are being trained to be genuinely more self-determining and rational. The mediating entity brings the two extremes together, the abstract ideal world of reason and freedom and the realm of unformed individual inclinations, in a manner that more powerfully realizes the potential of each side.

Many Marxist thinkers begin with that Hegelian account, but then add that there is a momentum in capitalism that eventually undermines and erodes not only the mediating entity that is the modern state but also all the other mediating forces that hold the culture together. Even within the modern state, some of these mediating, individuality-shaping forces may be left over from feudal, aristocratic, and religious practices or they may offer communal identities that buffer and temper the full force of the capitalist economy upon individuals. Marx himself, to take one example, wrote about the landed estates of Europe. While tenant farmers on the estates were clearly exploited, still there were traditional duties and loyalties that were mutual and that gave some degree of protection from purely capitalist energies. But over time, says Marx, the landowners came to see the land as purely an instance of capital, as a source of wealth to be invested at the best return possible, even if this meant expelling all the tenants, since a higher rate of return might be received with a different use of the land. That Marxist analysis might well be repeated in a somewhat analogous fashion today. Imagine an American living in 1960. He relates to the abstract political machinery of his nation through the mediating entities of the precinct captain, the ward chairman, and the local political party with its control over certain benefits and jobs. He joins a certain company in his early twenties and stays there for forty-five years, while sharing in a distinctive and lasting company culture with strong loyalties on both sides of the relationship. Perhaps he belongs to and is strongly loyal to a union that has its own cultural strength and identity. There are for this individual favored local department stores where he and his wife tend to be regular customers. He joins sports leagues, the Elks, the Knights of Columbus, the Rotary club, and so forth. His relation to the abstract realms of politics, economics, and society are thus through local mediating institutions that socialize him into certain community practices and that endure over time with recognizable cultural patterns. But the great engine of capitalism, so the Marxist argues and so Kornbluh points out as well, will in the long run thoroughly dismantle and dissolve such mediating entities, a process we are seeing the full effects of only today. Workers are thrown back on their own resources as immediate individuals. Companies hire and fire with little loyalty. People must become individual entrepreneurs and freelance contractors putting together temporary economic arrangements and then new ones. Jobs are outsourced as unions weaken and disappear. National television driven by capitalist-style campaign commercials undermines and displaces the local political parties and their modes of organization through precinct and ward leaders. Voluntary community organizations responsible for socializing individuals have less and less influence. Local department stores are replaced by more distant, more abstract economic entities engaged with online.

The operations of capitalism, then, so the Marxist will say, are gradually leaving us with two extremes in a tense opposition, with ever fewer and ever weaker mediating entities to cushion or buffer those tensions and pressures. At one pole are human individuals left more and more on their own in an isolated, atomist status as they nakedly face the ubiquitous abstract machinery of the economic and social world. At the other pole is an abstract economic machinery that operates at an ever greater distance, with an ever greater anonymity and autonomy.

We have, then, a further notion of immediacy stemming from that Hegelian and Marxist line of thought. It does not have to do with radical temporal compression, such that complex operations happen without the slightest delay, or with a direct, unprocessed expression of personal feelings. It concerns the status of individuals left on their own against powerful socioeconomic machineries, without mediating cultural entities to train, socialize, and receive them as part of a form of life that can give a more satisfying, more effective shape to their inclinations and desires. Kornbluh does make reference to such mediating “Hegelian” entities, but one would have expected a fuller treatment of them, given her theoretical background and interests. On this point there may well be a serious tension in her point of view. She presents her purpose for writing here as offering praise for, and an endorsement of, practices of mediation in the reading and writing of literature and in the assessment of society, as against a ubiquitous strain of immediacy that she associates with late, late capitalism. But Marxism in general, and the Frankfurt School in particular (which she favors), endorse a thorough dissolving and dismantling of mediating institutions and practices associated with liberal middle-class democracies, so that out of the vacuum of the resulting ruins, a radical transformation into a revolutionary socialism, with an entirely new mediating structure, will be possible. Benjamin did not have even the slightest sympathy for the Social Democratic parties in Europe that might have been successful mediating forces in the European political situation. His Angel of History has to look back and find only collapse, ruin, and destruction. That is why Marx himself applauded and encouraged the capitalist machinery and its working, because only that machinery was powerful enough ultimately to undermine and take apart the various feudal, religious, and bourgeois institutions. In his arguments against Ferdinand Lassalle and Lassalle’s dealings with Bismarck to bring substantial benefits to workers, Marx hated a worker-aristocrat alliance against the bourgeois class because it was the latter whose unfettered operations would further the internal contradictions of capitalism most intensely and so destroy traditional institutions. Marxism, then, seems one of the great forces against the sophisticated structures of mediation that Kornbluh seems to be supporting, at least in the area of aesthetics.

There are other tensions as well for Kornbluh’s account. The interplay between what is immediate and what is mediated can become quite complicated. Kornbluh clearly places herself on the side of mediation in her appeal to the theoretical frameworks of various European and American Marxist thinkers. But her actual presentation takes on many of the qualities she describes to the cultural style of immediacy that she is opposed to. Mediation is supposed to involve a critical distancing, a weighing and assessing, an examination of alternative explanatory frameworks. But Kornbluh is frequently attached, in an almost religious manner, to the thinkers and frameworks that she favors. Marx and Freud are her saints, a quality she extends to Jacques Lacan in his version of Freud and to the Frankfurt School in their version of Marx, as well as to Marxist-adjacent figures from contemporary American academia. There is little critical distance from, little skeptical scrutiny of, little sophisticated qualification of, the beliefs these figures put forward. The only argument needed is “As Marx said . . .” or “As Lacan said . . .” or “As Jameson said . . .” She seems to be asking the reader to be fully immersed and absorbed in the beliefs of these thinkers, and we will recall that immersion and absorption are, for her, signs of the capitalism-generated dominant culture or style that she opposes. Even her own writing style does not try for the cool clarity of distance but often sends the hazy abstractions of academic Marxist theory in a surging, engulfing rush upon the reader, as if experiencing that rush were more important than deciphering the relevant claims accurately. Again, that kind of surge is associated by Kornbluh with the immediacy she criticizes.

There is a similar outcome regarding a topic that is important enough for Kornbluh that she devotes a full chapter to it: circulation. She adopts the Marxist account about tensions within capitalism itself that will eventually make it collapse, especially regarding what Marxists see as an inevitable decline in productivity, where increases in productivity are needed to keep raising standards of living. With productivity flagging, Kornbluh claims, the capitalist world today resorts to an almost hysterical speeded-up circulation and recirculation of already produced items. Pipelines are built everywhere for the circulation of oil and natural gas. China takes raw materials from Chile and the Congo and brings them to China to make manufactured goods that are sent to America and Europe. (But does not the increased, more rapid circulation of these natural resources require greater production of them in the first place and not just circulation? Isn't that one of the causes of global warming?) Photos and messages are circulated instantaneously across the globe by the billions through social media. While production of worthwhile items takes labor and time, circulation can be much more economical and rapid, contributing to today's cultural style of immediacy, even as the intrinsic value of what is circulated may not increase.

It is not clear to what degree economic productivity is truly declining, as her account wishes to show in its expectation that we are heading for crises of capitalism, with a speedy, an almost hysterical circulation replacing genuine productivity. The introduction of far more rigorous free-market incentives in China, Southeast Asia, and India has brought hundreds of millions out of poverty, raising their standard of living substantially (far more than did Mao’s disastrous Great Leap Forward, which caused millions of deaths through famine). In the US, labor productivity percentage increases are inconsistent. They declined somewhat from 1970 on, then rose from 1994-2004, with the widespread use of digital technologies, declined a bit for a decade and a half and, at least at the moment, are rising again. So we do not really see a trend of catastrophic, crisis-creating decline and many predict that productivity will increase with the application of artificial intelligence. The rate of productivity increases in developing nations did start declining a bit after the 2008 crisis and some experts predict that by 2030 annual productivity increases for the globe will decline somewhat. The low-hanging fruit, as it were, of early productivity gains (increased education levels for the population, switching from low productivity subsistence labor to higher-productivity enterprises, for example) are less available and further gains, so it is said, require more intelligent government practices and policies, so that capital and labor can be invested in activities with higher productivity. Some will argue that where productivity-versus-circulation is concerned, information (such as that feeding AI networks) is what oil was to the older industrial world and that the generating of information through social media is not mere circulation but genuine production. Much of what Kornbluh calls mere circulation contributes to the actual manufacture of products and one wonders if the globe actually needs cluttering up with a lot more stuff. Her analysis here seems reminiscent of Marx’s predictions every ten years or so that some economic crisis was a sign that a complete collapse of capitalism was only a few years away. She wants to bring out a sense of things and meanings circulating in a surging tsunami across the globe that creates our style of urgent immediacy, as if we were partying very, very late and very, very desperately toward the end of a decadent era. But her claims about the actual working of the capitalist economy in the world today seem exaggerated, even if one surely finds significant flaws in the present operations of that economic form of life.

Her references to circulation bring up a rather different point. Kornbluh wants her overall account to assign this rush of circulation to the side of immediacy, as one more example of that cultural style. Yet it is through the efficient circulatory system of the capitalist economy that a massive degree of mediation occurs. Recall our Indonesian farmer whose apparently simple transaction is affected by happenings in Hong Kong, Zürich, Chicago, Brazil, Ukraine, and so forth. And we might remark on the somewhat peculiar nature of the circulation of the academic “theory” items that Kornbluh seems to favor. Graduate students and professors are trained to pass around concepts and phrases from Adorno, Benjamin, Lukács, Foucault, Marx, Freud, Lacan, Jameson, Deleuze, and many others as if this were an empty, almost frictionless circulation, without the whole system having to be tested frequently and rigorously against a full range of evidence from the world (not the cherry-picked kind). Such testing is how one encounters new energy from the pressure of reality itself; it is how there is a genuine productivity entering the system and preventing entropic decline. The circulation of “theory” concepts in the academic social sciences and humanities can easily seem like the circulation of ungrounded mortgage-backed securities during the financial crisis. If we are looking for an empty, energetic circulation not backed by any genuine productivity, that would be a good place to start.

If I have trouble with aspects of Kornbluh’s overall framework, one should grant that she is very good when presenting many of the practices in the academic and literary worlds today. She describes college writing classes that seem therapeutic sessions on the exploration of personal trauma rather than rigorous training in the traditional skills of being a writer. Instead of disciplining students into more sophisticated ways of grasping and describing reality, students’ own voices and language and style are now to be honored as nearly sacred. Autofiction, in which writers offer the actual happenings and feelings of their everyday lives without fictional structuring, invention, figuration, and larger framework-building, begins, says Kornbluh, to trump traditional fiction in the estimation of many young writers. Memoir becomes the dominant form of writing, even when the authors have accomplished little. In what is called autotheory, an author mixes an expression of feelings, sensitivities, and private mental happenings with reference to academic critical, feminist, literary, and queer theories that are treated not as tools of critical assessment but as contributing poetically, ecstatically, and personally to the expression of one’s subjective life and of one's distinctive identity. Kornbluh as a Marxist is devastated by these transformations of writing practice and of academic practice. Readers of such works take the privatized, personal, victimized point of view so easily and so inevitably that they lose the capacity to see larger social configurations in complex interplay and to develop the moral and intellectual resources for coming together in moral solidarity for useful collective action. So they are less ready than ever before for a Marxist transformation of the society. The most convincing and appealing chapters in the book are those devoted to Kornbluh’s keen understanding of the state of much writing in America (and in Europe) today. One bête-noire of hers is Karl Ove Knausgaard, who says right out that only the individual matters, and that only what actually happens to the individual matters, that nothing else is worth writing about and that there is no need to create fictions.

Kornbluh is considerably less convincing when she turns to her favorite theorists. One of them is Jacques Lacan, and his thought is behind a full chapter of the book. She makes much of Lacan’s distinction between an imaginary stage of mental development and a symbolic stage, and indeed her large-scale diagnosis will be that the cultural style of immediacy that she is lamenting is due to individuals experiencing the world at the Lacanian imaginary level, while her recommendation is for a much greater focus on social undertakings at the symbolic level.

How does she employ this distinction? The Lacanian imaginary stage involves not only images but also, more generally, reflections of the self in various forms of what counts as other. A paradigmatic case may be a child's seeing herself in the mirror, but one may also see oneself reflected in other individuals or objects that one is in contact with, so that a certain narcissistic structure governs this stage. For Lacan, the self’s early experience in the world is that of an extreme fragility, where that fragility is underlined by a sense of the self as made up of pieces and fragments that fail to achieve any kind of satisfying integration, so that fears of dissolution of the self are strong. But as reflected in the mirror or in other individuals or objects in the world, the self may seem to have an appealing wholeness. The attractive character of that reflected wholeness is behind the formation of the ego, claims Lacan. Its highest goals are to enforce a rigid, coercive unity upon the Heraclitean flux of the unconscious self and to establish well-determined, rigid defensive boundaries between what is self and what is other. But the ego thus formed, on Lacan’s account, is illusory and illegitimate, a defensive symptom that, in its defensive maneuvers, coerces and subjugates the more nimble, shifting, multiple movements of what Lacan calls the subject of the unconscious, which is more convincing as one’s proper self. That tendency toward rigidity, domination, and a subjugating wholeness also makes one impose false coercive unities on the things of the world and to find sameness and hard boundaries wherever one can.

In moving to the symbolic level, in contrast, humans begin to see matters not in terms of imagistic and narcissistic reflections of the self but in terms of shared concepts and shared linguistic grammars that determine rules for playing various language games (as in Wittgenstein). This is a realm, says Lacan, of pacts and of contracts, of a determination of allowable and non-allowable moves in shared social strategy games as if on a game board. Positions and moves are defined abstractly by the rules of the game, such that different players can occupy these positions or make these moves at different times, as opposed to the earlier, more dyadic relation of narcissistic reflection in the other. One might recall Kafka’s letter to his father in which he claims that his father’s body lies across the places on the social map such that his son cannot occupy them. This is to fail to see the world according to the grammars and abstract positions of the symbolic world, with sites that can be filled by different players at different times. It is important to Kornbluh that such rules defining a linguistic grammar make language games inherently social. One cannot play such a language game by oneself (as Wittgenstein argued).

In keeping this Lacanian distinction in mind, Kornbluh looks out on a world of social media that involves the circulation of billions of images, where social media platforms turn more and more to pictures and videos, icons and emojis, instead of to arguments. She sees how writing classes and fiction writing have devolved into confessional complaints about the self and about the refusal of others to honor one's identity and boundaries. She observes what seems to be an increasing narcissism in American culture and a decline of interest in projects of communal solidarity and in the collective, radical transformation of society. So, it makes sense to her to use the Lacanian imaginary-symbolic distinction to give shape and force to her cultural analysis. Things line up quite nicely for her, so she believes. On one side is a realm that is privatized, personalized, individual, narcissist, lost in a rush of images, focused on self-identity, and favoring a non-critical, non-distant immediacy of expression. On the other side is a realm of shared concepts supporting debate and agreement; of communal language games that can allow for a moral solidarity; of rich and complex social engagement with others; and of mediation through the availability of theoretical frameworks and critical distance.

Yet Lacan’s account of matters does not seem to line up in the way that she needs it to. She would like the Lacanian imaginary realm to be securely linked to the kind of individualism and privatization that she associates with capitalism’s tendency toward economic freelancers, independent contractors, and Uber drivers, without the solidarity of unions and other expressions of solidarity. But any look at history shows that the realm of images has been very frequently associated with collective identifications that strongly motivate group actions. That use of common images indeed has been the basis of a great deal of culture when it came to holding groups together and getting them to perform communal actions, both good and bad. So, Kornbluh’s mapping of things does not seem to work. On the other side, she as a Marxist wants the superior realm of the symbolic to be associated with group moral solidarity and collective action in pursuit of the good. But she fails to make a fundamental distinction. The symbolic realm is in one sense evidently communal in that rules, contracts, language games, grammars defining allowable and non-allowable moves, and so forth, demand agreement among the many participants. But in the actual functioning of these grammars, readers or players or thinkers might be acting as intensely selfish atoms rather than with any sense of solidarity regarding ends. To be social in the sense of requiring individuals to be playing the same game with the same grammatical rules does not mean at all that one will be looking for a moral solidarity with others and for collective endeavors for the common good. One might even say that capitalism matches up extremely well with the Lacanian symbolic. Clear rules of play defined over abstract positions that individuals can move into and out of with mobility seem to describe quite well the space of competition that allows for capitalist interaction, financial wheeler-dealing, complex legal contracts, and the like. One might note that Adorno makes a clear analogy between the conceptual realm that counts diverse worldly instances as the same and the economic system that makes different things exchangeable as having the same value. So for him the conceptual system and the capitalist economic system fit together smoothly; the Lacanian symbolic has no inherent connection with any Marxist communal goal.

Kornbluh also wants the Lacanian symbolic to support her particular notion of mediation, while the imaginary level supports experiences of immediacy. Yet simply having a set of shared concepts and shared grammatical rules defining interactive language games does not necessarily lead toward genuinely critical rational scrutiny, evidence assessment, rigorous self-criticism, and a curious, more impersonal examination of alternative accounts. (That would be true mediation in Kornbluh’s sense of the term.) Instead, as one notes if one looks at a great deal of “theory” in the academic humanities and social sciences, conceptual terms that seem fashionable for some reason or other are circulated nimbly like popular memes on social media. Shared concepts may not encourage critical reflection but just the opposite: one can maneuver them in games of intellectual fashion and status without worrying about what work they are doing to bring the articulations of reality more convincingly into view.

And there are further problems with using Lacan as a reference. Kornbluh inherits from him a radical and controversial view of individual selfhood that is not only unpersuasive; it also makes it much more difficult to defend the richer notion of aesthetic mediation that she is trying to support. Lacan, as we saw earlier, thinks that any attempt to bring wholeness, well-integrated functioning, well-defined self-other boundaries, and a distinctive overall style to the ego and its experiences is illusory, defensive, illegitimate, and destructive to the happiness of the Heraclitean mobile, multiple self. Synthesis, integration, and a rigorous discipline favoring sublimation cannot be valued. But a life like that, one that is so mobile and multiple not to have defining, reliable states of character and enduring virtues, one that is so changeable not to have long-lasting attachments supported by well-disciplined, well-integrated forms of life, is a miserable existence. Instead of giving a distinctive shape and style over time to one's mental life, one’s intimate attachments, and one’s achievements that are won through long years of labor, an individual is moved about here and there, willy-nilly, by whatever events in the environment happen to trigger chance reactions in the self. Lacan devalues the sphere of individual self-formation by associating it with a primitive narcissism. Yet the story of individual self-development is far richer than that and can end in quite sophisticated and worthy architectures of relating self and other, with a robust recognition of the individuality of others. By attaching oneself closely to Freud, as both Lacan and Kornbluh do, one misses the very fertile developments, since the time of Freud, in theories studying separation-individuation, attachment, and object-relations. A more mature and sophisticated handling of loss, separateness, aloneness, abandonment, metaphysical fragility, threats to dissolution of boundaries, fears of loss of identity, and pressures to sustain a rhythm and style of the self over time can produce profoundly rich and admirable developments in the individual’s self-formation. We might recall Hegel’s dialectic of master and slave, where very primitive notions of the other as something to be negated or dominated, as merely a mirror reflection of the self’s power, turn in a process of self-development into mutual recognition of each other's autonomy. Lacan leaves the ego undeveloped or else counts all development as illegitimate and defensive and as inevitably prone to destructive forms of domination.

Kornbluh wants to move on quickly to collective, social, perhaps revolutionary activity, while attaching the process of individuation to the deleterious effects of a privatizing capitalism. But without a very solid forming of individuals with integrity, self-sustaining power, psychological resilience, strength of character, independence of mind, maturity of self-other interactions, and so forth, there is little chance of promoting the kind of critical distancing and weighing that Kornbluh’s account needs if there is to be mediating activity worthy of the name. Otherwise, the collective activity that is encouraged becomes the circulation of fashionable concepts and favorite memes through shallow, conformist, weak, rather empty minds. Lacan is a terrible model to turn to; there is very little salvageable.

A further result of the turn to Lacan is also negative. It is damaging to Kornbluh’s fond goal of restoring attention to complex, sophisticated, mediating aesthetic structures in fiction and poetry, in place of immediate confessional outpourings. For such traditionally rich mediating structures on the aesthetic level (character development, figuration, complex references to literary history, a more critical distancing, and so forth) very often relate to matters of separation, individuation, loss, grief, shame, and other such matters on the individual level. From Melville to T. S. Eliot, from W. G. Sebald to Cormac McCarthy, from Elizabeth Bishop and James Merrill to Alice Munro, such matters of separation-individuation are often paramount. The trick is that these writers do not handle such matters by a nakedly immediate outpouring of feeling or of injury but by dispersing these issues far more subtly over a traditional field of references and styles (as does Merrill) or over a complexly imagined social world (as does Munro). Kornbluh cannot possibly restore the great richness of mediating structures available to writers today if she follows Lacan’s devaluing of individual self-formation and hopes that using the words ‘collective’ and ‘solidarity’ over and over in a positive manner will make up for the loss.

Kornbluh’s other great influence is Marx. As I have noted, she hardly brings a critical, distancing attitude toward this thinker. There is something almost touching in the way she, on occasion, quotes theoretical claims of Marx himself as if, as he formulated them, these are reliable statements of an original socialist gospel. Marx was always looking for contradictions in the logic of capitalism that would make it fail within a relatively short time. His analysis of surplus value and the falling rate of profit was supposed to pick out tensions that must lead to fatal crises in capitalism. Yet even Marxist theorists today are far more skeptical on such issues. Kornbluh finds both Marx and Freud to be intellectual heroes. Regarding the latter, for example, she follows Freud with little qualification in holding that depression arises from conflict between the ego and the superego even when, today, there are much weaker superego pressures on the young than in the past and yet a much higher occurrence of depression. (One suggestion might be that the very matters of self-formation studied by separation-individuation and object-relations theorists and dismissed or neglected by Lacan’s radical view of mental life are crucial to handling mental states such as depression.)

Nevertheless, we should take Kornbluh’s Marxist-style analysis of contemporary intellectual life seriously, for she raises very important issues about the character today of literary writing, literary theory, university writing classes, aesthetics more generally, and the everyday psychological life of individuals. She wants to show that the literary, aesthetic, and psychological features she is curious about are derived from the social and economic features of late, late capitalism. Arguments of this type have an inherent difficulty built into them. One begins easily enough with suggestive analogies between what is happening in intellectual life and what is happening in economic life. Then these analogies, however appealing they might be, must be strengthened into pervasive correlations and finally into genuinely causal relationships. A typical case is the following one. Kornbluh says the increased privatization and individualization of the capitalist economy affects the occupation of writers as well as those of Uber drivers, freelance coders, independent contractors, social media influencers, and the like. There are fewer magazines, newspapers, and publishing houses of the kind that once gave many writers a relatively secure economic position. They now have to string together different freelance sources of a relatively precarious income. So they do not have the kind of economic security that would give them time and leisure to investigate the intricacies of the larger social world as material for their writing. The only resources for content they can reliably turn to, given that economic precarity and lack of leisure, is their own mental states. So they will end up doing confessional writing about their immediate feelings of insecurity, victimization, and identity, since they do not have time or leisure to be curious about the wider world.

Yet can that analogy regarding privatization be convincing as a prominent causal relationship? It is true that in the 1950s a few writers could have a comfortable life as an official New Yorker writer and occasional novelist, and there were more magazines that paid well for stories and articles. But it is also the case that the massive expansion of university writing programs has made thousands of jobs for writers today that were not previously available, even if many of these are not tenure-track. Humanities programs today will often hire writing teachers instead of literary scholars, as they focus on the personal, confessional tendencies of their students. And the young today tend to very much overestimate the economic security of most writers in the past. Joyce was getting by on very little, teaching English, translating, and borrowing money from friends that he often did not pay back. Pynchon worked for a while writing technical manuals at Boeing and then lived cheaply in Mexico before making it as a writer. At the same time that Updike lived comfortably as a New Yorker writer, many thousands of writers struggled economically, failed to make much on their writing, and earned a living elsewhere. Many writers in the past who were economically secure became so not through generous societal support for their writing but through holding down regular jobs: Eliot as a banker, Stevens at an insurance company, Kafka as an official for workers’ disability insurance, and so forth. Such an option is readily available for writers today, with unemployment rates close to their historical lows.

Yet such writers of the past, even when they introduced autobiographical material, placed it in much wider, more complex, more historically rich, and more intellectually demanding frameworks. So the economic precarity of very many writers in late, late capitalism, in a culture that is especially attentive to and solicitous of the inclinations and wants of the young, cannot be a sufficient cause of the recent turn to the registering of a seemingly unprocessed outpouring of individual feelings. (Perhaps the argument might be put differently by Kornbluh, rather than focusing on economic precarity. If the culture keeps treating you as a private economic atom forced to maneuver on your own, then you may start taking a similar stance toward yourself, so that only the individual and what happens to the individual matter.) If one were truly interested in writing about wider social networks with different kinds of characters and psychologically and morally complex narratives, then four years at university and two years in an M.F.A. program would surely give one leisure to do considerable research, as did many recent writers who have written novels about Paris in the 1920s, New York in the 1890s, the American West in the 1970s, and the like. And if one were forced to work as an Uber driver, that could itself be an introduction to people with different stories and different styles of living who might be worth writing about. It seems true as well that even when writers such as Knausgaard, so central to Kornbluh’s account, become quite well off financially, they still work on the topic of the immediate experiences of the self, rather than using their wealth to explore more complex socioeconomic narratives. So, the former choice was not originally a faute-de-mieux choice forced by economic precarity.

Additionally, if the capitalist system really is the defining mechanism for selecting and incentivizing certain character traits useful for itself, then the culture of confessional immediacy, complaint, and identity is hardly what would be selected. Capitalism wants workers who are punctual, conscientious, hard-working, low-maintenance, and devoted to the firm or business, not workers concerned mainly with the state of their feelings. It would be odd if the logic of late capitalism, once its ubiquitous power had made individuals shallower and easily malleable to its workings, should then turn these individuals into writers obsessed with autofiction and autotheory. On the other side, one might argue that an obsession with one’s own mental states and one’s identity is an artifact of a strongly consumerist economy (rather than one trying to generate economically desirable traits in workers). And there must be something right in the claim that it is the speeding up of an intensely circulating economy that makes it natural for individuals to expect and to favor experiences that offer their meanings and their psychological appeal immediately, without the slow unfolding of more complicated, more sophisticated, and more socially and historically intricate patterns. Kornbluh’s point about the ubiquity and colonizing power of capitalist forms of interaction is backed by changes at universities over the last few decades. Students are treated more like clients or consumers who must be placated rather than as candidates to be formed into a particular type of well-educated person, with certain accompanying character traits and capacities.

I find it persuasive that there is a subtle interplay, rather than any one-sided causality, between the features of our present-day self-conscious cultural undertakings and the features of the underlying economy. Each side surely influences the other. Unlike with Marx’s very strong emphasis on economic causation, we observe considerable autonomy, though certainly not independence, in the logics of development of the two sides. One might examine this matter by looking at a couple of the historical occasions when the cultural sphere and an economic sphere defined by capitalism interacted.

One instance is the obvious one of the Protestant Reformation. It is slightly odd that Kornbluh herself does not introduce this comparison, since there are interesting parallels regarding her issue of immediacy. Here, too, a couple of related meanings of immediacy converged. There was a keen attention to the immediate mental experiences of individuals. This showed itself in a religious emphasis on diaries, on personal confession to God, and on an unmediated experience of the Bible’s divine address to humans, so that individuals had to read the Bible in their own languages instead of using the mediation of a priest. It showed itself as well in a philosophical emphasis, in Descartes, Locke, and others, on epistemically immediate experiences that could be the foundation of knowledge. There is a further interesting parallel. One could supposedly have a secure and trustworthy epistemic foundation if one merely registered one’s immediate sense impressions in a non-processed manner. Others could not, in that situation, question or assess one’s claims negatively. Once one introduced broader metaphysical frameworks and conclusions, only then would falsehood enter. There is a peculiar parallel with that thought in the autofiction and autotheory idea that if one simply makes one’s immediate confessional claims in one’s own authentic voice and one’s own authentic telling, then others have no right to evaluate what one says.

A related sense of immediacy associated with Protestantism, once again parallel to Kornbluh’s account, is that all the great mediating factors of Catholicism (the priestly hierarchy, the sacraments, the institutions, the historical continuity) were called into question and devalued in favor of the immediacy of a direct relation to God. Just as individuals on Kornbluh’s account will more and more face the abstract socioeconomic machinery of capitalism as naked individuals, so for radical Protestantism individuals would face the divine realm as naked individuals without mediating institutions to aid them.

It is a historical cliché that the psychological qualities associated with the Protestant Reformation became interestingly linked with the rise of capitalism. But the psychological qualities in question were not generated by capitalism itself. They were the result of several centuries of religious and philosophical developments. Medieval nominalism so emphasized the absolute freedom of God, with everything depending on God’s totally free election of who would be saved and who would not, that the mediating institutions of the Church had to be placed under very great pressure that eventually they could not bear. Facing their own extremely burdensome pressure as individuals when it came to salvation, men and women recognized that they could do nothing on their own to influence God’s decision to save them or not. Humans are such fallen sinners, so they believed, that they could acquire a range of virtuous qualities only if God had already decided to include them among the saved. So there was a strong incentive, even as one knew that one's good behavior could not make God save one, to exhibit as fully as possible one’s possession of the relevant virtues, since this indicated that one was on the side of the saved. Punctuality, hard work, frugality, and financial saving were among these qualities, so one’s religious orientation supported capitalism, even if the causation generating the characteristics in question was not ultimately an economic one.

A further interesting case is recalled by Ann Douglas in The Feminization of American Culture. She describes the time in 19th-century America when women joined with a liberal Protestant clergy to form a cultural style that dominated writing and publishing for decades. On Douglas's account, the novels, stories, and poems published by women had several characteristics rather like those that Kornbluh attributes to her culture of immediacy. The aim of such writing seems to have been an immediate triggering of preferred sentiments in both writers and readers. What is crucial is not what actually happens but the sentimental emotional states generated in the consumer of the scene. There is an emphasis on the keeping of diaries, on a monitoring of morally relevant states of mind that the character may have had that day, as one moved from meditations on how one stood in relation to God to states of moral feeling that were satisfying in themselves. One often finds, claims Douglas, a significant degree of narcissism in these writings, in that experiences are not important for what they say about the world being experienced but for the particular emotions they are intended to trigger. Ordinary emotional responses such as mourning turn into exhibitionistic displays of one's feelings. There is virtually no attention, Douglas notes, to the social and economic machinery that was transforming the culture at this time or to the larger patterns of history. In triggering and expressing preferred gratifying mental states, there is little tough-minded investigation of the human psyche such as one finds, for example, in Melville or in Nietzsche. The enterprise of writing is rather a religious and moral undertaking. The poems and novels glorify the soft power of women to raise the moral standard of those around them and to transform morally frail men out of their masculine toxicity of violence, drunkenness, and irreligiosity. Female characters are in a strong alliance with clergymen in their undertakings and usually turn out to be the stronger figures who are usurping the power roles once held by the clergy. There is almost no mediating self-critique that attains some real distance from the gratifying moral-psychological stance that these writings display and reward.

It will of course be true that economic factors will be influential in the emergence of this women's writing culture. Douglas points to their changed role, a more sentimentally domestic one, in the developing industrial economy. But she makes it clear as well (as we saw in the discussion of the Protestant Reformation) that there was a distinctive culture behind this social phenomenon that she describes, a culture with a real degree of autonomy based on a certain momentum of history. Economic changes helped in the liberalizing of American culture, but the history of Puritanism in America had its own particular shape. The great harshness and terror of truly Calvinist patriarchal religion were being very much modified by a culture that was speaking of God more as a soothing, helpful parent with feminine qualities than as the Calvinist divine. That religious change allowed a greater role for women in churches and also left more liberal clergymen needing new social allies, now that their earlier cultural rule had been severely weakened.

I propose that we assess some of Kornbluh’s claims in the light of the lesson suggested by those two examples: that there might be cultural happenings that can best be understood only partly as effects of economic developments. Culture may have a historical momentum as well as patterns of transformation of its own, beyond that economic causality. In this regard I want to return to Hegel’s notion of political and cultural forms that are mediating in that they do two things. They embody higher-level ideas of reason and freedom in an actual historical and material existence and, at the same time, they raise up the scattered, indeterminate, arbitrary givenness of individuals’ wants and inclinations into more enduring, more sophisticated, more elevated, and more admirable traits of character and patterns of mental life. A crucial part of Hegel’s account is that what he calls the realm of immediacy (of arbitrarily given, indeterminately arranged desires and inclinations) is not worth very much in itself and is certainly not to be honored as having some kind of sacred, untouchable value. It is only as disciplined, trained, transformed, integrated, and raised up into higher forms by a distinctive mediating culture that these immediate mental items come to have a genuine worth. One will notice right away how different, even opposite, this is from the precepts of the university writing courses that Kornbluh describes. For the latter, honoring the uneducated voice and unprocessed feelings that students bring to the classroom is the favored principle, not a disciplining in sophisticated and objective writing techniques that allow the expression of more complex and more subtle mental states.

It is an interesting point that Nietzsche, so different a philosopher from Hegel in many respects, has considerable in common with him here. Those who (inaccurately) think of Nietzsche as an anarchist or nihilist are surprised to discover, when they actually read him, his consistent praise for cultures that had the confidence, the strong traditions, and the psychological strength over time to discipline their members, especially the young, quite harshly in particular hard-earned virtues and forms of mental life that they had found to be the admirable traits of their culture. He speaks positively of the age of French classicism, of the Venetian aristocracy, of the high stage of Islamic Spain, and of the Roman Empire itself and the continuity of its shaping a very particular form of life. His strong dislike of modernity, socialism, liberalism, and utilitarianism is due to what he feels is their inevitable tendency, in the long run, to support a leveling, homogenizing process that leaves individuals in an empty mediocrity of unstructured mental life, much like what Kornbluh describes under her concept of immediacy. Nietzsche can surprise again by being a proponent of rather severe practices of habit and character formation. He writes in praise of a sublimating rechanneling of immediately given sentiments, so that these are ordered into mental activities capable of greater force and sophistication, and capable as well of more elevated and more compelling intellectual and aesthetic gestures.

In Hegel and Nietzsche, then, one favors mediating cultures confident enough in their forms of life to quite strongly discipline the young in the virtues, habits, skills, and powers needed to lead that form of life. Confidence is the key here, because the minds of the young are not developed enough to be able to comprehend at first just what is the value of the materials they are forced to read and study. It may take years before the desired intellectual and ethical virtues have taken sufficient hold so that individuals can truly appreciate the exercise of these virtues in and for themselves. What happens if the trainers start to lose their confidence in, and their commitment to, those virtues and those achieved patterns of life and thought?

So that is what needs to be explained here in terms of the immediacy-versus-mediation issue, not the effects of a speeded-up capitalist system of circulation and privatization on the universities and on the practices of writers. Somehow, the willingness of traditional institutions and forms of life to achieve that Hegelian-Nietzschean disciplining and transforming of the disordered, arbitrary immediacy of the mental states of the young has been lost. Instead of confronting students with a very rich structure of intellectual and aesthetic work that they must accommodate themselves to if they are to count as learned, the governing principle is to meet the students where they are, to allow the widest room for a free choice of classes, to let them focus academically on their most personal feelings and sense of identity. If students fail, it is because professors have failed to make the material appealing enough or have failed to figure out individual schemes of motivation. It is not because of character and behavioral failings on the part of the students, their inability to order their minds in accord with an intellectual framework that is foreign to them at first and too sophisticated to be immediately appreciated.

One can see quite readily various elements of this cultural change. In some real sense, the direction of accommodation or of deference in the culture has been radically transformed. For most of history, the young were asked to accommodate or adjust their behavior to rigidly defined systems of acting, thinking, and valuing, systems that did not take their particular feelings very much into account. But parents and professors now, instead of representing such a well-defined ethical, psychological, and intellectual world, must try to adjust their undertakings to the feelings and attitudes of the young, blaming themselves if the young feel unrecognized, sad, or confused. An important change thus takes place in education. A traditional belief is that a central part of an educational system is not just the intellectual maturing of the young but also continuing to hand down, as with a baton in a relay race, the great achievements of human generations even into the quite distant past. One must accommodate one's own disordered and undeveloped personal feelings to a very great architecture of thought and feeling that has been passed down and added to across history. It is a very different approach to education that supposes that courses, books, and educational practices in high schools and universities should accommodate practices to the already present feelings and inclinations of students.

Authority thus weakens as confidence in the passing on of a very particular form of life wanes. As the enduring mediating cultures lose their legitimacy, one is left with an unformed immediacy of feeling, as Hegel or Nietzsche would have predicted. The culture that Kornbluh describes then results. The universities themselves have been chief theoretical contributors to the change in question. Studies in the humanities and social sciences make the values, attitudes, and abilities that a Hegelian mediating culture might enforce on the young through disciplined training come off as authoritarian, coercive, and illegitimate. The set of literary, philosophical, and historical texts that embodies such a Hegelian mediating culture is said to be so essentially biased, to contribute to so many unjust structures of power, that we must undermine and dismantle rather than endorse them. They encode not generally insightful investigations of the human condition but the self-identity issues of white males of European descent. Of course, such white men have indeed had twenty-five hundred years to develop their intellectual and aesthetic frameworks to a level of extraordinary sophistication, subtlety, and power. So many centuries of competition and selection pressures had to produce profound philosophical ideas and intricately woven aesthetic schemes that together probe complex human psychological states and our metaphysical relation to the universe. But that achievement, it is claimed, brings with it such a high cost in terms of bias, privilege, illegitimate distribution of power, and so forth that it cannot be the basis for a proper training of the young at the present moment. The enduring mediating cultures that transfigured the unformed, arbitrary, awkward immediacy of individual mental life into more elevated, admirable, distinctive patterns of thinking and feeling are too illegitimate, it is claimed, to retain their power, in spite of the praiseworthy qualities they often display. If other groups without that twenty-five-hundred-year history generate intellectual and aesthetic products that stick closer to an individualist immediacy, that is only to be expected.

Hegel, for his part, remains a great apostle of mediation. In his Philosophy of Right, he works through institutions and forms of life such as property, exchanges, contracts, criminal justice punishments, legal personhood, morality, family, religion, civil society, and citizenship in a nation. These are all, so he claims, features that contribute to the emancipation of individuals from the immediacy of psychological life into a realm of free, rational self-determination, and thus into a genuine autonomy. These mediating structures are paramount in his account of individual freedom, as their educational, disciplinary, transformative, elevating capacities bring us out of our unfree immediacy. Those trained perhaps by Foucault and the Frankfurt School will raise very strong suspicions about such mediating activities. Such activities are forms, they will say, not of emancipation but of subjugation and coercion, of making individuals adjust to arbitrary power, so that happiness for the individual becomes impossible.

I am, I should say, roughly on the side of Hegel and Nietzsche here. Even as we admit, as we have to, that unfair biases and privileges are built into the intellectual and aesthetic cultures that have traditionally been imposed on students, there is no substitute for their psychological and metaphysical subtlety and profundity, nor for their aesthetic ingenuity and originality. Twenty-five hundred years of rigorous selection pressures will produce certain results. The best strategy, for members of previously underrepresented or unrepresented groups, is to master those mediating intellectual and aesthetic worlds and to adapt their capacities and achievements to new human situations, as opposed to confronting the tradition with an immediate expression of personal injury and identity.

I think an argument to that effect is worth making but I will not pursue it further here. I am interested rather in why this is an argument that Kornbluh herself does not make. She wants very much, we saw, to defend a notion of thoroughly mediated experience against the cultural pull toward immediacy. And she mentions every once in a while the loss of the social and economic “middleman” structures (unions, voluntary organizations, company cultures with lifetime loyalties, and so forth) that once mediated between naked individuals and the abstract universal machinery of the economy. Why, then, does she not turn to the Hegelian-Nietzschean idea of confident cultures willing to shape and discipline the immediacy of individuals’ contingent psychological states until they develop into more reliable virtues and traits of character and more sophisticated intellectual and aesthetic undertakings? Her Marxism, as we have seen all along, stands in the way. For those confident cultures, especially on the aesthetic side, were often generated in and through older economic systems, and Marxists are not usually defenders of the typical sorts of cultural mediation that developed during the feudal, aristocratic, and especially the bourgeois forms of life (though Marx himself was well-trained in the German educational system). Virtually all of the mediating forms that we listed above from Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, intended as they were to raise individuals out of their own forms of immediacy into an achievement of rational self-determination, are to be dissolved under Marxism. To the extent that the all-powerful capitalist machinery keeps eroding, undermining, and dismantling all the stabilizing structures of the social world, Marx is a firm ally of capitalism. Marxists must let capitalism exercise its unequaled capacity at dissolution and destruction so that eventually all the mediating and stabilizing elements disappear and one is left with an absolute tension of two extremes: the naked immediacy of individuals and the abstract divine-like machinery of capitalism. Only with such an absolute tension will pressures for a radical revolution be evident, a revolution that will establish a very new socialist form of mediation. Adorno and Benjamin of the Frankfurt School, as I indicated earlier, offered not the slightest support for, or identification with, the representative parliaments and the Social-Democratic political parties that were, for very many Europeans then, the principal mediating institutions between their private individual lives and their abstract ideas of freedom and justice. When Kornbluh favors mediation, she means being able to take a critical distance from the present situation we are immersed in, not the Hegelian institutional mediations so crucial to advanced societies.

In the end, she is a literary theorist and her most interesting recommendations concern the teaching of literature and the teaching of writing in schools of creative writing. Here her preference for mediating structures stands her in good stead. In the field of literature, the aesthetic structures at issue for her are those that do not pretend to any unprocessed immediacy but transparently impose artificial patterns and sophisticated literary forms on the literary materials. In that way, individual experience, to the extent that it enters into the writing, is very much processed, interpreted, and re-ordered for larger purposes. These literary forms would include, in fiction, complex plots, character development, figuration such as metaphor and analogy, and a highly distinctive style; and, in poetry, traditional forms, rhyme schemes, and the like. Instead of a single first-person point of view, there might be a third-person telling that transcends limitations of space and time, that takes over diverse characters’ minds through free indirect discourse. Anything that causes the reader to slow down and to have to work at interpretation is, in Kornbluh’s scheme, good. Whatever places the social machinery’s speedy operations on brief hold and clogs or sabotages the automatic happening of an immediate response is desired.

These recommendations are fine, but they are limited by their political purpose. Kornbluh wants fiction and poetry to open themselves to an investigation of large social landscapes and of diversely situated individuals so that the operations of the social machinery and of human life today become much clearer. Moral solidarity and collective action, rather than individual probing of one’s feelings, might then result. Solidarity and collectivity are always on the good side in her account, while individualism gets assigned to the Lacanian imaginary, to privatized capitalism, to narcissism, and to the regime of immediacy. But many of the most interesting and powerful mediating aesthetic structures are those that are associated with psychological projects of individual self-formation. As I mentioned earlier, Lacan leaves the self in a primitively immature state. He resists approving of its efforts to develop more compelling and more advanced structures of separation-individuation as well as a sophisticated architecture of self and other, such that a more integrated and well-formed working of the ego results. If Kornbluh truly wants to bring a rich experience of reading literature back to university classrooms, she should be open to the ways that projects of individual self-formation may be very intensely mediated in their aesthetic forms and may offer students ways of thinking that are far more challenging and admirable than those involved in expressing one’s feelings in an unprocessed manner. (That training may offer more challenging, more effective strategies against depression and the fragility of identity than will an immediate expression of unprocessed feeling.) Otherwise, her recommended program for literary training risks turning into something like socialist-realist propaganda for a particular social and political future. The favored critical mediation will have very definite and very evident ideological roots that impoverish the intellectual and psychological achievements that literature might provide.

We might see the point I am making if we look briefly at three writers. James Merrill, in one of his finest poems, “Lost in Translation,” is engaged in the sort of enterprise that the “immediacy” writers whom Kornbluh criticizes are also engaged in. In his forties in Athens, the poet is thinking back to the difficult emotions he felt at twelve when his parents were divorcing and he is thinking as well of the failure of his lengthy relationship with a younger Greek man. Yet the poem has the richest sort of mediation in its aesthetic structures. It plays off a work by the French poet Valéry and off a translation of that poem into German by Rilke. There is intricate figuration in that an orientalist jigsaw puzzle the boy was solving at twelve becomes a metaphor for the fitting together of word-pieces in the making of the poem three decades later. Issues of gender identity come through with extreme subtlety in the separating of different colored puzzle pieces and in the character of the painting that the puzzle registers. The German umlaut over a vowel in Rilke’s translation becomes an owlet looking over an evening perspective as the poet is looking back from the distance of age, as if a deflating reference is being made to Hegel’s owl of Minerva that flies at dusk. There are dozens more of these pleasing aesthetic patterns. The larger question raised is how well aesthetic achievements of certain complex kinds can help confront and master tendencies toward dissolution and loss.

Or take Eliot’s “The Waste Land.” It is, the more one reads it, an almost desperate attempt to come to grips with issues of separation-individuation, loss, boundaries, and identity in the context of Western cultural and religious institutions that themselves may not have separated adequately from the rather cruel West Asian rites at their origin. The fear is that those Western mediating institutions may not be strong enough to do their jobs in relation to the individual. And has the poet himself separated effectively from the maternal psychological and religious world of his childhood? But as with Merrill, issues that today might have led to a mode of unprocessed confessional immediacy are intensely mediated through much of Eliot’s knowledge of literary and cultural history: Vergil, Ovid, Augustine, Rome versus Carthage, Dante, Shakespeare, Marvell, Baudelaire, Whitman, Wagner, Fraser, Verlaine, the Bible, and many more. The artifice of the aesthetic patterns is pronounced, so that one is placed at something of a distance from any immediacy of emotive expression, as Kornbluh desires. And there is reference as well to the larger social background, to a postwar weakening of traditional social structures, as she also desires.

A more recent example would be the stories of Alice Munro. Quite often in these stories an adult woman, perhaps in Vancouver, is going through personal events that make her relive a complicated, ambivalent separating from her rural upbringing in Ontario. Once again, these issues are richly filtered through the subtle psychological interaction of several characters in the contemporary social world. When Georgia in “Differently,” after having an affair and separating from her husband, wonders later on whether she should have acted differently, the story’s many details make that answer not at all evident as one observes, with some skepticism, a certain period of social and sexual liberation in Vancouver.